A recent New York Times article by Jennifer Preston examines some of the concerted efforts to coordinate this first-hand news sharing by an organization called Global Voices, "a volunteer-driven organization and platform that works with bloggers all over the world to translate, aggregate and link to online content." Preston writes:

Soon after the earthquake and tsunami struck Japan on Friday, the volunteer bloggers for Global Voices in East Asia put together special coverage of the devastation, sharing citizen videos and translating posts on Twitter, including calls for help from people stranded on the upper floors of buildings. Over the weekend, with fears fueled by the prospect of a second explosion at a nuclear plant, they monitored the conversation on the social Web, reporting how people were exchanging information to keep safe and questioning the use of nuclear energy in an earthquake-prone region.

“Our job is to curate the conversation that is happening all over the Internet with people who really understand what is going on,” said Rebecca MacKinnon, a former Tokyo bureau chief for CNN who founded Global Voices with Ethan Zuckerman, a technologist and Africa expert, while they were fellows at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society. “We amplify, contextualize and translate what these conversations are and why they are relevant.”In this era of new spreadable media, sometimes good things happen as a result. Michael Martinez of CNN reports on a Japanese student in California who discovered that her family, who lived in one of the communities hardest-hit by the tsunami, was safe--by seeing their message in a YouTube video.

Bradley Blackburn of ABC News reports on the role of social media in communicating about the disaster and, in some cases, responding to it. Similarly, Dorian Benkoil writes on PBS' MediaShift about how rich and multifaceted information flow about Japan's events have been:

The past few days, sitting at home and in my office in New York, it felt like I had more information and contacts at my fingertips than I did then as a reporter in Japan. The morning I learned of the quake, I had a TV connected to digital cable, an iPad, a Blackberry and a web-connected computer in my living room.

I flipped among ABC, NBC, MSNBC, Fox, CNN, and BBC on TV. An iPad app gave me video of quake alerts in English and other languages from Japanese national broadcaster NHK. I dipped into the Twitter and Facebook streams.

A photo slideshow on the front page of the New York Times only a few hours after the quake gave a sense of not just the depth of destruction but also the geographic breadth. The towns being mentioned in captions spanned multiple prefectures (similar to states).

I was able to watch Japanese TV network TBS live via a Ustream link I was referred to in a "Japan Quake" page assembled by my New York-based friend and media colleague Sree Sreenivasan.

Benkoil continued,

Some connections were possible this time only because of technology. I was able to observe New Jersey-based relatives of my Tokyo-based translator friend express love and relief that she and her family in Japan were safe. My friends in the U.S. and elsewhere used Facebook, Twitter and text messages to ask me about my loved ones in Japan, which let me reply in a way that was much easier to handle than in the previous era.

The media and communication technology of course do not change the scope of the disaster but do change the way we are able to experience and share it.

Perhaps most importantly, social media have become a primary channel for raising awareness and gathering funds for relief efforts. An article by Matt Wilson of Ragan.com provided an early summary of where to go if you would like to help, discussing how Twitter, Facebook and text messaging are being used to spearhead relief fundraising, and AFP reports that Zynga, the company behind the "FarmVille" game (a Facebook app), raised $1 million within 36 hours for Save the Children's Japan relief efforts:

Zynga asked users to donate money through the purchase of virtual goods in FarmVille, CityVille, FrontierVille and its other games. All of the proceeds from the purchase of sweet potatoes in CityVille, radishes in FarmVille or kobe cows in FrontierVille are going towards Save the Children's relief efforts.

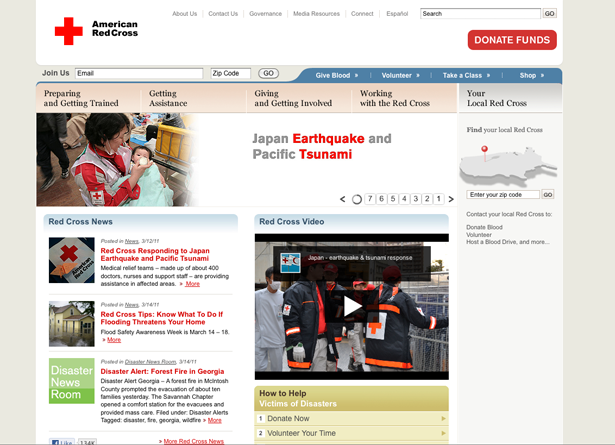

Apple has set up an option on iTunes to allow users to donate from $5 to $200 to the American Red Cross and the Red Cross has launched a campaign on Facebook through the social media giant's Causes function.The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reports that The Salvation Army and the American Red Cross are also raising funds for the Japanese crisis by accepting $10 donations via text message.

To donate to the Salvation Army, which has had a presence in Japan since 1895, text "Japan" or "Quake" to 80888.

Text "RedCross" to 90999 to donate to its fund set up in response to the disaster. The American Red Cross is coordinating with its Japanese counterpart, which is leading the organization's efforts in the disaster area.