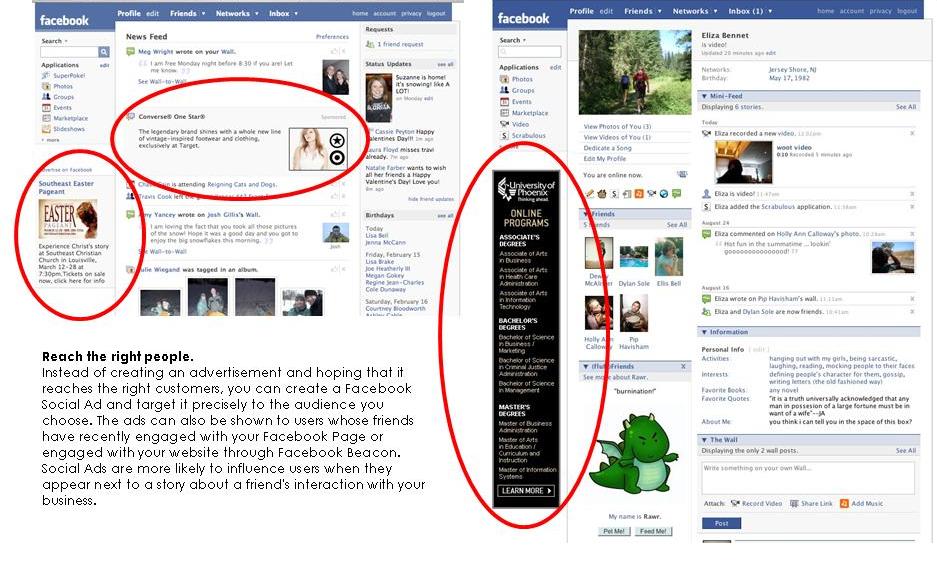

Print publishers are having trouble transitioning to a digital business because they are still trying to do business the old way. Yet things are much different in the online world and there is no reason to do the business of selling advertising the old way.Most of us are vaguely aware that our personal data is vulnerable to being used by marketers to target us. We notice that the ads on Facebook seem to strangely match our interests and location and age brackets. Is this a coincidence? Not at all. And it goes much, much farther and deeper than Facebook.

Print publishers have to conduct focus groups and ask readers what they read, what they like, and who they are. The online publisher knows all of that all of the time, and can apply a lot more creativity to building a thriving advertiser community. There is a tremendous amount of user data that can be mined and converted into valuable information.--Tim Foremski

Building databases about customers is hardly a new business, nor is it illegal or illegitimate. Telemarketers, political candidates and advertisers have been gathering information about people for years. Online, it's what Web users exchange in return for free services and content.

But the information is becoming far more precise. It's one thing for a marketer to know you're 40 years old and subscribe to travel magazines; it's another for them to know you're leaving Saturday for a week in Italy.--David Goldman

In an extensive Time magazine article on Data Mining: How Companies Now Know Everything About You, Joel Stein writes about the data-marketing firms like Alliance Data, EXelate, BlueKai and RapLeaf.

Each of these pieces of information (and misinformation) about me is sold for about two-fifths of a cent to advertisers, which then deliver me an Internet ad, send me a catalog or mail me a credit-card offer. This data is collected in lots of ways, such as tracking devices (like cookies) on websites that allow a company to identify you as you travel around the Web and apps you download on your cell that look at your contact list and location. You know how everything has seemed free for the past few years? It wasn't. It's just that no one told you that instead of using money, you were paying with your personal information.An October 2010 article in CNNMoney by David Goldman declares that "Rapleaf is selling your identity":

Rapleaf knows your name, your age and where you live. It knows your e-mail address, your income and what social networks you use. It knows your likes and dislikes. And it makes money by selling much of that personal information to advertisers.

Of course, Rapleaf is far from the only company that does this. Acxiom, ChoicePoint, Quantcast, and BluKai also collect and sell your data, as do many others. Google (GOOG, Fortune 500), Facebook and other Web companies also gather data about you in an attempt to target very personal ads.

But Rapleaf was thrust into the spotlight this week after the Wall Street Journal reported that the San Francisco-based company obtained Facebook IDs from many of the social network's apps and sold those IDs to advertisers -- even from users who requested that data be kept private.

By merging a user's Facebook ID with other data about them, Rapleaf gave advertisers a detailed window into many Web users' personal information. In a recent blog post on the issue, Rapleaf called it "a serious potential privacy risk."

A May 2010 Time article by Dan Fletcher on Facebook's everchanging privacy rules discusses the increasingly easy availability of so much personal information that we purposefully or inadvertently put online, and how Facebook as well as all of these other companies are benefitting from our data:

There's something unsettling about granting the world a front-row seat to all of our interests. But [Facebook founder Mark] Zuckerberg is betting that it's not unsettling enough to enough people that we'll stop sharing all the big and small moments of our lives with the site. On the contrary, he's betting that there's almost no limit to what people will share and to how his company can benefit from it.Consider that every site that you join to which you enter personal information, everything that you buy online, and every website you visit provides information about you that is gathered and archived by these data mining companies, allowing them to create profiles on you (accurate or not) that then enable advertisers to specifically target you as they focus on very particular demographic groups. If you discuss your pets on a pet owner's forum, you may begin seeing ads for pet food and pet care. If you visit health care pages on certain medical conditions, you may begin to receive emails advertising medications. If you exhibit an interest in a particular style of music or certain artists, other artists of similar style may market to you. Even the ability of social networking sites like LinkedIn to recommend "people you may know" is remarkable, creating lists of potential connections based upon wide range of personal data about you, not all of which you have necessarily entered into their specific database.

In this July 2014 article, This is How Your Financial Data is Being Used to Serve You Ads, author Sam Thielman explains how your shopping purchases--especially at all those stores where you get loyalty cards--are tracked by data mining companies and then interfaced with personal data they buy regarding your credit card spending habits and purchases, your TV and movie viewing through your cable company, even your medications via your pharmacy purchases. What can they do with all of this information, you ask? Well, lots of things you probably don't want to even think about (and you thought your life behind closed doors was private, didn't you?). But a primary focus right now is for advertisers to customize their marketing to enable them to target you, with great precision and efficiency, regarding products they can predict you will want.

Originally published March 2011. Updated 18 July 2014.